University of Chemnitz, 28.11.2025

Bilingual Workshop (German/English) of the Working Group “Social Movements and Police” of the Institute for Protest and Social Movement Studies in collaboration with the research project “Local Publics and Social Conflicts Surrounding AI Security Technologies” and the research project “Visions of Policing”.

Organization: Katharina Fritsch, Philipp Knopp, Fabian de Hair, Stephanie Schmidt

See the Call for Papers as pdf here.

Please send a short abstract of approx. 300 words to philipp.knopp@phil.tu-chemnitz.de by July 15th 2025.

The police gaze has always been a subject of interest for the social sciences. Early studies

drew attention to the superficial (Sacks 1972) and selective nature (Feest and

Blankenburg 1972) of police vision. These analyses often focused on everyday patrols and

encounters between citizens and police officers in face-to-face interactions. However,

the extensive mediatization of visibility (Thompson 2005) also affects the police in general

(Goldsmith 2010) and protest policing in particular (Ullrich 2014). In recent years, studies

on the police and protest have increasingly drawn attention to new socio-technical

arrangements shaping visibility at protest events and beyond (Melgaço and Monaghan

2018). Nevertheless, it appears that a fundamental transformation of power relations

between protest and policing has not yet occurred. Instead, an open struggle for the new

mediatized visibility emerged, in which tactical and technological innovations of police

and protest reinforce each other resulting in constant reconfigurations of repertoires of

contention and control (Ullrich and Knopp 2018).

New technologies of surveillance and sousveillance (Mann, Nolan, and Wellman 2003)

have also proliferared in everyday life. Smartphones, a wide range of new recording

devices used by the police (bodycams, drones, dashcams, etc.) as well as technologies

for image processing and analysis have contributed to an increasing number and new

types of images depicting conflict and violent situations. The availability of large amounts

of data on online platforms and automated surveillance (Andrejevic 2019) are another

socio-technical driverfor the contemporary reconfiguration of visibility/power relations in

the policing of protest and everyday life. Police forces have been experimenting with facial

recognition (Selwyn et al. 2024) and predictive policing (Egbert and Leese 2020) in some

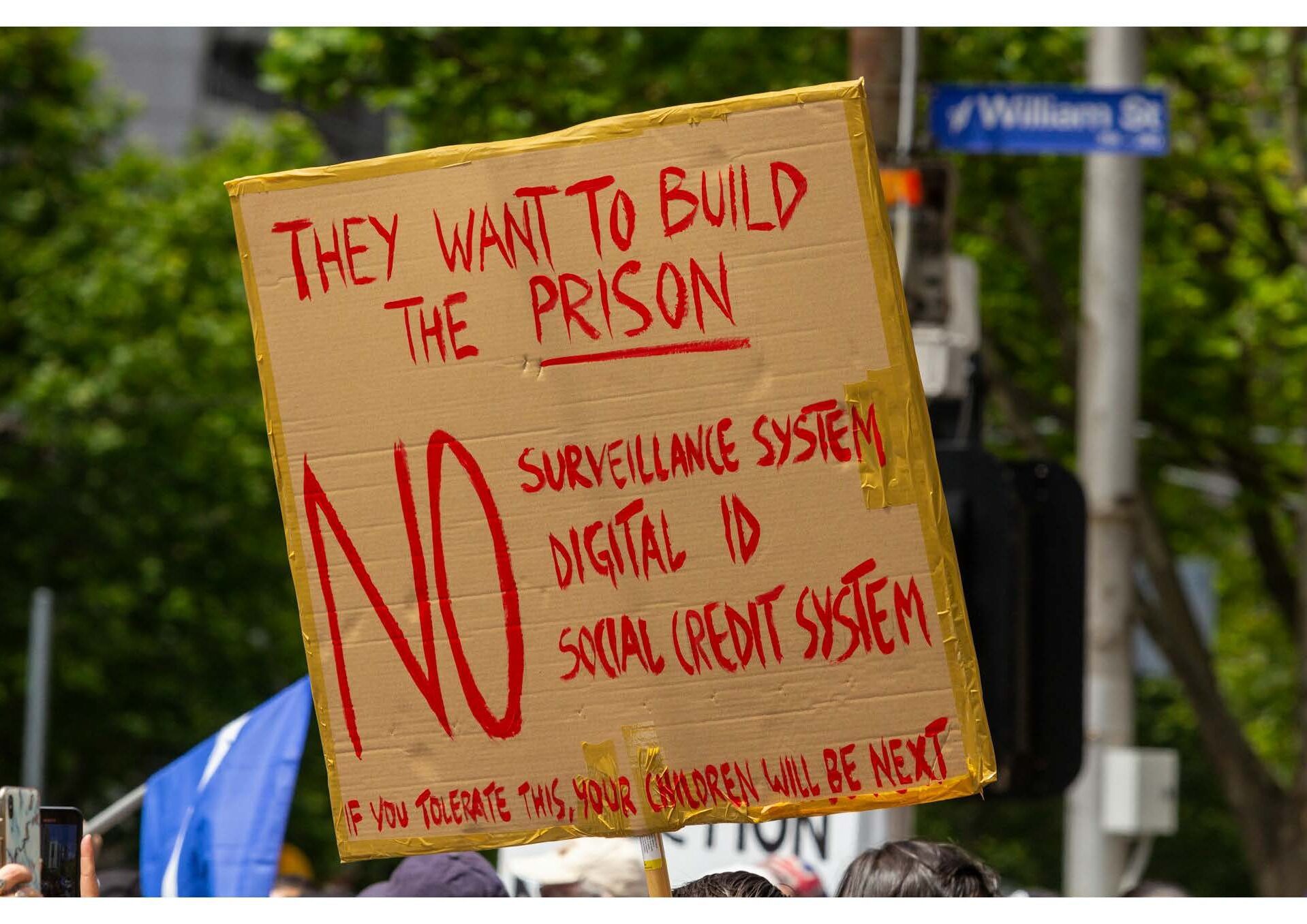

places also in the context of protest policing (Binder 2016). However, the new surveillance

technologies themselves have become a subject of criticism and protests, igniting public

controversies and become key forces for the regulation of high-risk security technologies.

However, digital media have also rendered the police practices in everyday life and during

protest events more visible for public scrutiny. Images of police violence have drawn

attention to issues of intersectional inequality reflecting broader perceptions of injustice.

Against the backdrop of these new developments, it is crucial to remember that

surveillance ans sousveillance are never isolated. Rather, they are situated in socio-

technical assemblages that significantly shape its meaning, use and impact. Visibility

relations are therefore always embedded in political discourses, intersectional structures

of inequality and technological ecologies. These broader configurations of surveillance

practices, police suspicion and selective treatment of citizens do not only reflect existing

inequalities but differentially (re)produce inequality and shape the experience of

marginalization, stigmatization and violence. Thus, the technologization of the police

gaze not only affects the relationship between the police and ‘criminals’, but also raises

the question how automation and AI affect the relationship between the police and

different social groups and the citizens police shall protect.

This year’s annual workshop of the Working Group “Social Movements and Police” of the

Institute for Protest and Social Movements Studies is therefore dedicated to the following

questions, among others:

- How is the police gaze reconfigured with new media and technologies?

- What new forms of suspicion emerge in the context of artificial intelligence and

ubiquitous datafication? - How is surveillance taken up as an issue by social movements? How do protest

actors and other social groups under surveillance adapt their practices to the new

socio-technical visibility? - How do protest actors navigate the tension between political and securitizing

visibility? How do police officers and police forces navigate their new visibility in

everyday life and during protests? - How are ‘smart’ surveillance technologies changing police suspicion practices in

general? - Which social, economic and political relations drive the technologization of police

gaze? Which are the central public and police discourses shaping it? - How do protesters contribute to the reconfiguration of surveillance practices?

- How do police officers and other surveillance professions interpret the recent turn

to AI supported surveillance? - Which new practices of counter-surveillance, sousveillance and criticism towards

unjust police actions occur in the context of new media and AI?